Collection Name

About

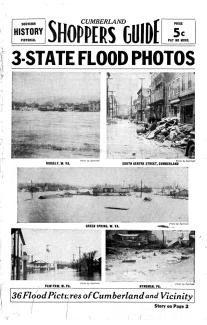

Souvenir History of Cumberland's Flood

CUMBERLAND SHOPPERS GUIDE

Price: 5 cents

Offices: 105 Henry Street

Published weekly in Cumberland, Md. by: Stanley Fields and William B. Kaldor

Richard T. Renshaw, City Editor

Delivered at the door of 15,000 homes in the Tri State area.

Advertising rates on request

The Shopper's Guide will be glad to consider for publication items submitted by its readers.

The photographs in this issue which are credited to Eyerman may be purchased individually from the Eyerman Studios at 59. Mechanic Street. Those credited to Eleanor Gerkins may be purchased at 501 Beall Street.

Here, conveniently on one page is the story of the Great Flood of 1936—the flood that prostrated Cumberland, Queen City, and industrial leader of Western Maryland. Here is the story off the Catastrophe, a story that opens with rainy Monday, March 16, and closes upon Cumberland, calm, and on the way to Recovery after the flood waters had receded. Here is a story simply written, set forth chronologically in all its appalling detail, describing the situation as Cumberland met it and faced it. This is a page that you will want to save, together with the entire picture section, for reference in future years for the complete story of the Great Flood of 1936. The editor.

----

By RICHARD T. RENSHAW

Forecast

Because it had long been common belief that Cumberland was afflicted with a flood every twelve years, and because the snowfall was unusually heavy in the winter of 1935-36 while January and February had been a series of alternate hot and cold spells, a spring flood had been predicted as early as February, 1936.

Several false alarms had come as the result of thawing snow but it was a heavy and protracted rain which began to fall on Monday, March 16, continuing until late Tuesday night that caused Wills Creek to rise and inundate a large section of the City of Cumberland.

While the floods of 1924 were serious, particularly the May flood of that year; they were caused by the rising of the Potomac River, into which Wills creek empties at a point just below Cumberland. In 1936, the Potomac was not dangerously high. The trouble was due to the creek being unable to empty into the river fast enough to disgorge the water which poured down from the mountains.

Early Tuesday morning, March 17, Cumberland authorities began to feel uneasy. By communicating with points throughout the "Creek Section" it became apparent that water was rising at a dangerous rate and a flood was on the way.

Throughout the day crowds gathered on the Baltimore street bridge to watch the rising water, in spite of the heavy downpour.

Fire Chief Reid C. Hoenika began notifying property owners along Mechanic street and in the low-lying parts of town to prepare for high water. At this time the water was still nearly eight feet lower than flood stage, but was rising rapidly.

Precautions were taken but no one suspected the proportions the flood was to assume.

The day wore on: the rain continued; the creek rose; and a feeling of impending tragedy pervaded everyone. Baltimore street soon resembled an ant hill; with people scurrying here and there, boarding up windows, placing sand-bags, and doing everything possible to prepare for the worst. If they had only known it, they were wasting energy for nothing in the world could have withstood the force of the torrent that was soon to follow.

By 3 p. m. every store along the lower end of Baltimore Street had suspended business. Employees rushed helter-skelter putting merchandise in high places. Unfortunately, the high places proved not high enough in many cases because people thought the water wouldn't go higher than in 1924.

Arrival

At 4 p. m. word began to circulate that Wills Creek had overflowed its banks at the Narrows and that upper Mechanic Street was flooded to a depth of 12 inches. This marked the actual beginning of the flood.

At Baltimore and Mechanic streets the clear rain water that had been running in the gutters all day slowly changed to a muddy color. A trickle of brown that widened into a broad band on each side of the street began to come.

For nearly fifteen minutes the sewers absorbed this overflow but they were soon filled and the water turned the corner, running lazily along Baltimore street, ankle deep. The bands on each side met. Mechanic street was under water. Center and Liberty Streets were in the same condition, but slightly less deep. Watchers at the Creek reported that it was still rising, and the rain continued.

It began to grow dark. Fear that the electric lights would soon go out grew. Candles became precious and even matches were in big demand.

The City Fathers realizing that Cumberland was in for a siege created flood headquarters at City Hall from which to direct emergency activities. The Red Cross, with its usual dispatch, set up emergency headquarters at the State Armory.

Water was two feet deep in the streets by this time, and was still rising. Every pair of hip boots in town was sold. Volunteer workers had to wade, soaked to the skin, in icy water.

As the water crept higher, many phones went dead, throwing switchboards into confusion. Trouble crews worked frantically disconnecting lights on dead phones so the operators could answer legitimate calls.

By five p. m. Mechanic, Center and Liberty streets were virtually tributaries of Wills Creek. Crossing them, even in a boat would have been a hazardous undertaking. City Hall was soon cut off by the rising water, and phones there went dead. Headquarters was washed out.

Sixteen were trapped in a building on South Mechanic Street. Several men were marooned in a cigar store on Center Street, and later nearly drowned when the water broke the plate glass windows and swept them out into the stream. Nearly every store on Baltimore street held refugees.

As the night wore on with the water growing higher, rescue crews were able to get food into the buildings by pulleys but evacuating the trapped victims was impossible.

Washouts

By six o'clock rumors of bridges being washed out were going the rounds. Nearly every dam within 100 miles was said to have broken. A siding with 13 freight cars on it did wash out. One railroad bridge gave way. No dams broke.

Trains, buses, and cars were stranded. Communications were cut off. The city was isolated for the duration of the high water, save for radio station WTBO, which obtained permission from the Communications Commission through Senator Millard E. Tydings, to remain on the air alt night.

With headquarters cut off, the police found themselves temporarily without leadership but gallantly carried on. The Fire Department moved its equipment to higher ground. Flood water, inundating all bridges, made it impossible to get to or from the West Side except by walking across the B. & O. viaduct.

Hotels outside of the flooded area were packed, as were all other available rooms and sleeping places. Hundreds of refugees spent the night in the Armory where they were cared for by the Red Cross, who estimated the number of families washed out at more than 1200, close to 6,000 people. These were in addition to those who were only temporarily cut off from their homes.

As word of the flood spread, offers of aid began to pour in from state, federal, and local officials of other communities.

8 p. m. found water over the Western Maryland railroad bridge at Baltimore street, and an ominous sag in the line of cars standing there told officers that the bridge had buckled. No one was allowed to approach within a few hundred feet of the structure which was expected to give way momentarily.

Mayor George W. Legge called on the National Guard to help preserve order and to prevent looting of damaged property. In a very short time they had mobilized and were swinging into action aiding the local police, and the special officers who had been sworn in. The town was under semi-marshall law.

Meanwhile, the raging water was doing a first class wreckage job. Inadequately secured windows smashed under the impact of the water. Quickly the contents of these stores were swept out into the general confusion, to bump and slide along adding impetus to the water's charge Soon articles of every description, including stoves, refrigerators, pianos, showcases, gasoline storage tanks and household furnishings could be seen bobbing along like straw on the crest of the waves.

Although it was Election day, and the polls had long since closed, nobody knew and few cared who had been elected. It was purely and simply the day of the flood and nothing else was of even minute importance. Not even St. Patrick.

Barricades in front of stores gave way without much of a struggle against the force of the current. Water rose to a depth of ten feet and more in many places. Even Baltimore street was covered by more than six feet at the height of the flood.

Rehabilitation

No sooner had the flood started to subside than Water Department employees began to rush the work of repairing water lines. The Street Superintendent quickly mobilized crews to clean away enough of the debris to allow trucks to gel through the devastated sections. The City Engineer made a hurried survey to estimate the damage. The WPA Administrator received permission to use laborers on clean-up work. Whole companies of CCCs were rushed in to help. Scores of workers were hired by the city, and private contractors were pressed into service with both men and their equipment.

The damaged area was set apart and roped off. No one was allowed to enter except on business Unfortunately the first set of passes was issued indiscriminately and a second and a third set had to be issued -before all the curiosity seekers had been weeded out.

The local company of National Guards were relieved by a company from Hagerstown. Mayor Legge issued a proclamation closing all places selling beer and liquor every evening at nine. All restaurants outside the flood area did a landoffice business. No theatres escaped the flood, and as a result Cumberland was under a blanket of gloom with nothing to relieve the tragedy.

Reconstruction work progressed rapidly. Plate glass poured into town by the truckload and quickly replaced the 300 boarded up windows of the day after the flood.

Merchants piled debris on the curb and trucks hauled it away. Mails which were delayed for several days returned to normal. Salvaged merchandise was offered to the public at give away prices. Bargain hunters snapped it up. Citizens took their losses cheerfully.

The National Guard was recalled. State Police took over the job of patroling the crippled area. A few days of frenzied activity saw an end to the worst. The State Police were recalled. The special officers were relieved of their duties. The flood area was opened. Business returned to normal. The Great Flood of 1936 faded into the past and became History. Cumberland marched ahead!!