Collection Name

About

Breaking Barriers

February 29, 2004

Area residents recall an era of integration.

Just 50 years ago black patrons weren't allowed to enter the front doors of some theaters in downtown Cumberland. Local restaurants required African-Americans to dine in separate areas from whites, or they banned black customers altogether.

But perhaps worst of all, until the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 decision in a case that became known as Brown vs. the Board of Education, black children could not attend the same schools as white children.

"We lived on Mechanic Street, and there were very few black families living there at the time, so I had a lot of white friends," recalls Shirley Corthron.

"They didn’t understand why I couldn’t go to the movies or restaurants with them. At the Maryland Theater we had to enter through the back door and climb all the way up to what we called the peanut gallery which was even higher than the balcony area," she said.

Corthron said by the time the theater finally became desegregated, she had long lost interest in attending motion pictures there. "We went to the drive-in movies", she said.

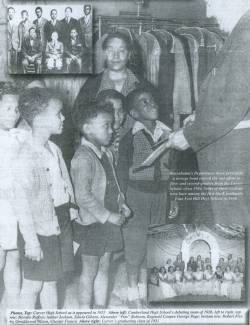

Like many African-Americans from the local area, Corthron attended Carver School on Frederick Street in Cumberland. Approximately 117 to 125 students from first through 12th grade were educated at Carver each year from 1922 through 1960. The black students were basically taught the same subjects as white students, although Principal Earle Bracey eventually changed the curriculum focus from academic to more vocational-type subjects which he felt would better prepare his students for jobs after graduation.

Carver’s student population hailed from towns as far away as Moorefield and Petersburg, W.Va. Carver was the first and only four-year high school for black students in this area, said Mary Louise Jones, Carver historian and director of support services, research and assessment for Allegany County schools. She said teens from distant towns in West Virginia often boarded with families in the Cumberland area so they could attend Carver. Some went home on weekends, but others spent most of the school year away from home. Jones’ family took in several students, mostly relatives from the Petersburg area.

But shortly after the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling, schools like Carver were emptied as black students were finally able to join their white counterparts at public schools. The Supreme Court decision stemmed from a Topeka, Kan. case that began in 1951, challenging the segregation of public schools. The challenge was initiated by Oliver Brown, father of Linda Brown, a black Topeka third-grader who had to walk a mile through a railroad yard to get to her school, even though a white elementary school was located much closer to her home. When Oliver Brown attempted to register his daughter at the white school, the principal refused.

Brown and other concerned parents then sought assistance from Topeka’s branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. On behalf of Brown the NAACP requested an injunction to stop segregation in Topeka schools. The local school board became the defendant in the case. After a two-day hearing the Kansas U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the school board.

The Brown case was appealed to the Supreme Court in October 1951 and was combined with similar cases from three other states. It took three years and some lengthy discussions involving whether the 1868 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution covered desegregation of schools before a final decision was made in the Brown case.

Finally in 1954, thanks largely to the efforts of a black lawyer from Maryland, Thurgood Marshall, who headed the NAACP, the Supreme Court ordered schools across the nation to desegregate. In Cumberland, desegregation took place in phases for the Carver students. High school students were the first to leave in the fall of 1955, and primary students were the last to be moved into local white schools in 1960. The older students entered Allegany, Fort Hill or Beall High schools.

Jo Biggs Hall of Frostburg remembers her first day at Beall High. She was a junior in the class of 1957, one of the first black students to graduate from Beall. “I walked to school with my twin sister, Jane. We met some other black students down the block and walked to school together,” she said. “I didn’t know anyone at Beall, but we felt welcomed there”. Biggs Hall said the new arrivals were given a tour of the high school by some white students. “I remember there were so many more lockers with more room than we had at Carver,” she said.

“I really didn’t have a lot of problems at Beall,” said Clarence Hall of Frostburg, who was also a 1957 graduate. “I already knew a lot of the kids and they accepted us right from the get-go,” he said. “It was the laws that had kept us apart. Otherwise we always felt like we were a part of the community.”

But Hall said it took some time for other areas of society to catch up with school desegregation. “I ran on the Beall track team and played soccer,” he said. “Once we were on a trip to the University of Maryland at College Park and stopped at a restaurant. I had to go into the back to eat. I'll never forget that. It really tears you down,” said Hall. “You’re one of the best runners, but you couldn’t eat with the rest of the team. Today my kids can’t understand that,” he said. They say, “Daddy, you’ve got to be kidding.”

Things have changed since that time. “I was 17 when we moved into Allegany High,” said Corthron. “It was a little scary. I didn’t know what I was going to run into, though I was treated well there. But after the Allegany High football games my friends would want to go someplace to eat, but I couldn’t go,” she said. “So they wouldn’t go either. Instead we’d go home and play records or something. I’ve passed on my experiences to my children,” she said. “I tell them, You don’t know the opportunities that you have now. There were no such things as scholarships back then.”

Two of Corthron’s daughters took their mothers advice and earned masters degrees. Kia, a playwright, received her degree from Columbia University. Kara, who loves acting, earned her masters at New York University.

Judge J. Frederick Sharer, who was vice president of Fort Hill High Schools 1956 graduating class, said the integration with black students didn’t draw a lot of attention at his school. “But I’m sure there was some apprehension for those who were being thrust into a much larger school,” he said. "There were about 300 in our graduating class. This was a new situation for them and they probably had some uneasy feelings."

Sharer noted that segregation had never existed in the local Little League and Hot Stove League baseball teams since the leagues were founded in 1949 and the early 1950s. Many of us already knew each other before the schools were integrated, said Sharer. "It’s sort of a stretch of the imagination that we played ball with each other in the summers, but weren’t allowed to learn together in school."

Jones, who joined the graduating class of 1956 at Allegany High, said there was also a sadness about leaving the teachers at Carver. It didn’t seem to be clear what was going to happen to them. "So we were concerned." Jones said some of the black teachers were absorbed by the school system, while others retired. But there were also some who had to find work elsewhere.

Text: Cumberland Times-News