Collection Name

About

Local ties to the Underground Railroad

Teresa McMinn, Cumberland Times-News

Mystery, folklore and patchy records surround the reasons that Samuel Semmes and Samuel Denson ended up in Cumberland.

At face value, Semmes was a Confederate slave owner, while Denson had escaped bondage.

A closer look, however, suggests they might have shared a common goal.

While there are few records of Cumberland's involvement in the Underground Railroad, local families of former slaves for generations have talked of tunnels beneath a church that acted as a stop on the way to freedom across the Mason-Dixon line.

Semmes leaves his church

According to Western Maryland’s Historical Library, Semmes was a lifelong Roman Catholic, successful attorney, farmer, influential community leader, state appeals court judge and bountiful land owner.

He wanted his slaves to receive Holy Communion at St. Patrick’s, but the church priest refused to cooperate.

So Semmes offered to finance 30% of the construction cost for a new Emmanuel Episcopal Church as long as his slaves could receive the Eucharist there and be seated in a balcony during religious services.

“This proposition was accepted with two drawbacks,” the records state. “First, the Semmes slaves having been baptized Roman Catholic, refused to become Episcopalian. Second, black members of Emmanuel, who had been a part of the congregation from the outset, were made to sit apart.”

Here’s where the questions begin.

Why would Semmes give his slaves a say in the matter?

Denson arrives in Cumberland

Documents show a slave gallery was included in the new Emmanuel Parish, consecrated in 1851.

The church was built at one of the city’s highest points over deep trenches that Col. George Washington and other soldiers dug as an escape route from the battlefield to nearby Fort Cumberland, which was a military and economic center in the mid-1700s during the French and Indian War, and became a rally point for British forces under command of Major General Edward Braddock.

Roughly 100 years later, in 1849, the cornerstone of the church was laid and its rector, Rev. David Hillhouse Buel, who was already active in the Underground Railroad in other areas of Maryland, realized the tunnels under the church could be used as a stop for escaped slaves heading north to be free in Pennsylvania.

Meanwhile, Samuel Denson, an escaping teenage slave from Mississippi, somehow made his way to Emmanuel Parish.

Buel appointed Denson as church sexton.

At that time, a steam line ran through the tunnels from the furnace beneath the church to a nearby academy, and rectory.

“It was a natural part of the sexton’s job to pass between these buildings day and night,” Emmanuel’s website states.

“Oral history” indicates that escaped slaves would rest beneath the church, receive food and aid from Buel, Denson and other abolitionists and conspirators.

“When night fell again, they would go down the tunnel that led them through the basement of the academy and into the basement of the rectory,” the website states. “Then they would go out the rectory cellar door, which in those days was in an unpopulated part of town, and meet up with the transportation that would take them across the Mason-Dixon Line, just (four) miles away, or up another route that would lead them to the Land of Freedom.”

By the mid-1800s, the tunnels had been around for a century.

Semmes sold Emmanuel the church building lot on the hill in 1850.

At that time, he not only owned property surrounding the church, but regularly attended religious services there.

Additionally, it was well known that slaves were running from northern Maryland into Pennsylvania.

How could Semmes not know if slaves were escaping beneath the church?

Brothers take opposite sides

Semmes, born in Charles County in 1811, had two siblings. His older brother by two years, Raphael, would become a lawyer, and an officer in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1860 and the Confederate States Navy from 1860 to 1865.

Their sister, Henrietta Thompson Semmes, born in 1813, died when she was about 10 years old.

According to Southern Historical Society records, their father was Richard Thompson Semmes, fifth in descent from the first American ancestor, Benedict Joseph Semmes, of Normandy, France, who came over with Lord Baltimore in 1640.

Their mother was Catherine Hooe Middleton, a descendant of Arthur Middleton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Their parents died when the boys were very young, and a brother of Richard Thompson Semmes, Benedict Semmes, cared for the children.

Maryland State Archives show that Benedict Semmes was a physician elected to the Maryland House of Delegates from Prince George's County.

In 1828, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives, where he served from March 1829 to March 1833.

The Semmes brothers also spent time with another uncle who was a prominent banker and businessman in Maryland.

It’s unclear how or why Samuel Semmes came to Cumberland, but records show he drafted most of the charters of the pioneering coal companies in Allegany County, and served as state senator from 1855 to 1866.

The book “Civil War Maryland: Stories from the Old Line State,” states Samuel Semmes “was an ardent pro-Unionist.”

And in the book “Wolf of the Deep: Raphael Semmes and the Notorious Confederate Raider CSS Alabama,” Samuel Semmes “chose the Union side in his free-labor town of Cumberland and Raphael Semmes was “disappointed and mortified” over his brother’s defection.

“For four years the brothers, very close since childhood and the early deaths of their parents, stayed out of touch,” the book states.

Following the Civil War, Raphael Semmes was held a prisoner of war and eventually charged with treason on December 15, 1865, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

“He was released from his imprisonment in the New York Navy yard three months later,” the Trust states.

Raphael Semmes carried out the remainder of his life working as a professor at the Louisiana State University and released “Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War Between the States” in 1877.

At some point after the war, Raphael Semmes wrote a letter to his brother.

Samuel Semmes wrote back and expressed relief that his brother was safe and healthy after his service in the Confederate Navy.

"My own course has been a neutral one,” Samuel Semmes wrote. “I was opposed to the secession movement of the Southern States, and so long as the United States government in its declarations of policy professed to limit itself to its duty in maintaining the Constitution and laws of the United States, I approved the conduct of the administration; but from the time the policy was avowed that peace could only be restored upon condition that the institution of slavery was surrendered in all the revolted States, I then saw that the conflict would be a protracted, bitter and destructive one.”

Samuel Semmes further describes “the evil I began to dread after the first year of the war, and from that time forward I seriously doubted whether the liberties of those who adhered to the United States would not be better secured in future by the success of the Confederate States."

He also commented on the legacy of President Lincoln.

“The motives and influences which sustained the United States' government in its giant-like efforts to subdue the Southern States, were not only of the most selfish and vindictive kind, but purely sectional and kept active and raging by the fiendish spirit of abolition,” Samuel Semmes wrote. “The late president Lincoln instead of being the great man … was neither more nor less than the weak tool of a party."

Raphael Semmes in his memoirs had written that the North used slavery as an excuse for the Civil War, which was actually based on tariffs.

Was Samuel Semmes making the same point in the letter to his brother?

‘What we think happened’

Lynn Bowman is author of multiple books on African American history including her recent work, “Ten Weeks on Jonathan Street, the Legacy of 19th Century African American Hagerstown, Maryland.”

She is an adjunct associate professor of English and speech at Allegany College of Maryland and also serves as a member of the state’s Commission on African American History and Culture.

Cumberland was connected to the Underground Railroad, she said.

Bowman talked of free blacks, as well as slaves, who had permission to move about the area.

The activity made it easier for escaping slaves to blend into the community and go unnoticed.

“Samuel Denson is an example of that,” she said.

Denson also remained in Cumberland rather than traveling into Pennsylvania where he could have been free.

“We know that he stayed. He had a family,” she said.

“The oral history matches the few facts we have,” Bowman said. “People went to unbelievable lengths to escape.”

There are records that show slaves owned by Samuel Semmes were baptized.

“Many blacks learned to read because of learning catechism for their (first Holy Communion),” she said.

Additionally, “it’s absolutely feasible” that Samuel Semmes participated in helping slaves escape through the tunnels beneath the church, Bowman said.

Further, Samuel Semmes had a cousin in Denson’s hometown of Vicksburg, Mississippi, she said.

Did that connection help Denson get to Cumberland?

“There are so many things that are possible,” Bowman said.

Cumberland native Ron Growden was in seventh grade when local schools went through desegregation.

Decades later, after he retired as an Air Force pilot, he began studying the history of Emmanuel Parish.

Today, Growden is chief docent at the church, which receives many visitors that want to learn more about the tunnels.

He is careful to tell folks who visit the church, “This is what we think happened,” when he talks of Denson and Semmes.

“Maryland being a slave state, it was illegal to even participate in the Underground Railroad. So, records were not kept,” he said. “(Our information) is circumstantial to a great extent.”

Growden talked of another part of the old fort’s defense works that ran from beneath the east end of the church down the hill to the banks of nearby Will’s Creek where rail lines came together at the terminus of the C&O Canal.

It was a poor area that provided a hiding place for someone on the run.

Additionally, records indicate the canal’s towpath that wound through Virginia and met the Potomac near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, was a major line on the Underground Railroad.

“You had all these ways of getting here,” Growden said of Cumberland.

Escaping slaves who had reached the city were instructed to hide in the area and await a signal for their next move, he said.

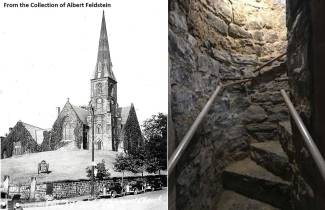

Underground Railroad - Emmanuel Parish basement steps

These basement steps lead to tunnels beneath Emmanuel Parish in Cumberland, Maryland.

It was Denson’s job to send them a message by ringing the church bell in a coded way, and then bring them up the hill by the old fort’s earthwork, through an iron gate that led them through a passage to safety under the church, Growden said.

“(Denson) had a real role here and the community was used to seeing him here,” Growden said.

Some folks doubt that the tunnels beneath the church were part of the Underground Railroad, because “nothing has been written down,” he said.

“I choose to believe it. It makes sense,” Growden said. “Perhaps it’s a bit romantic of me as well.”

It should be noted that research undertaken in recent years by Dan Whetzel and other historians call into question the accuracy of the historical accounts, timing and relationship among Samuel Denson, the Underground Railroad and Emmanuel Episcopal Church. As always, and without real documentation, this should be considered within the context of the oral history and folklore as it has been passed down to this time. We have posted some of this recent research elsewhere on this website.

Emmanuel Parish church postcard, courtesy of Albert Feldstein.

Basement steps lead to tunnels beneath Emmanuel Parish in Cumberland. Photograph by Teresa McMinn

For more on Samuel Semmes see Samuel Semmes