Collection Name

About

The most commonly accepted historical account as to how Negro Mountain received its name can be traced to the 1750s. Colonel Thomas Cresap and his black body-servant, "Nemesis", were tracking a group of American Indians who some say had attacked a settlement near present-day Oldtown in Allegany County. It was said a family had been murdered and horses stolen. Others write Nemesis was requested to accompany a ranging party that regularly scouted the frontier in order to protect homes from attack. Either way, Nemesis had a premonition he would not return.

One evening while cleaning his weapon, Nemesis told Cresap that he would not be coming back. Cresap thought Nemesis was afraid, or going to runaway. He "jestingly" offered Nemesis the opportunity to remain behind with the women if he was afraid. Nemesis replied he was not scared, but simply stating a fact. Cresap's party pursued the Indians over present-day Savage and Meadow Mountains, to the next mountain where a fierce battle ensured. Nemesis fought bravely, was killed, and buried on the site.

Cresap named the mountain in honor of Nemesis' race and it has ever since been known as "Negro Mountain." Nemesis was said to have been a large and powerfully built man. "Negro Mountain" remains a memorial and historic tribute to the presence of this black frontiersman.

Based upon research undertaken by historian Francis Zumbrun, a letter sent to the Maryland Gazette in 1756 by Thomas Cresap explains the naming of the mountain. It states that it was a free black man who had accompanied his volunteer rangers during the French and Indian War and who had died heroically in the battle while saving Cresap's life. Zumbrun, a retired forester for the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and local historian, also notes that the mountain is named in honor of one of the earliest "free" black frontiersman on record in American colonial history.

---

The naming of a mountain

By Francis "Champ" Zumbrun

"In the Appalachian Mountains there is a monument to a black frontiersman. It was established in the 18th century by his fellow frontiersmen and is the type of monument that generals, explorers and politicians strive to inspire for themselves. This monument is a mountain ... Negro Mountain." Lee Teter

Lee Teter is a nationally known artist. One of his paintings, "Shades of Death," depicts Col. Thomas Cresap comforting the mortally wounded, heroic black frontiersman.

Four articles written in 1756, recently discovered in two Colonial newspapers of that time, the Maryland Gazette and Pennsylvania Gazette, shed new light on the origins of the place named Negro Mountain in Garrett County.

In 1756, the French and Indian War was in full force in Western Maryland. The French and the Indians were emboldened by the defeat of Gen. Edward Braddock's army the summer before. In the late winter and spring of 1756, an estimated 300 to 400 French and Indians attacked settlements in and around Fort Cumberland.

On April 23, 1756, Thomas Cresap Jr., the son of Col. Thomas Cresap, marched out of Fort Cumberland leading 40 volunteer rangers, "all dressed in Indian apparel and red caps." Their mission: to travel west along Braddock Road as far as Fort Duquesne to eliminate the Indian threat from the region.

About 15 miles from Fort Cumberland, at Savage River, near and on present-day Savage River State Forest, Cresap's rangers encountered and engaged the Indians. Mishaps occurred, resulting in the tragic death of Thomas Cresap Jr. His men quickly buried Cresap's body at a place near where Braddock Road crosses Savage River, and returned back to Fort Cumberland.

On May 24, 1756, one month after his son's ill-fated journey, Col. Cresap marched out of Fort Cumberland with his sons Daniel and Michael and 71 volunteers. Their purpose was to continue the mission Thomas Cresap Jr. started.

One of the few black frontiersman of the era, said to be "old" and a person of "gigantic stature," marched with Col. Cresap. Early documents do not give us his name, but they do say he was a "free negro" who volunteered to fight for the English against the French and Indians.

Also marching with Col. Cresap's forces was Christopher Gist, leading 18 soldiers and 13 Nottoway Indians. Cresap's formidable company of more than 100 men followed the same route Thomas Cresap Jr. planned to take one month earlier along the Braddock Road.

On the first four days out, Col. Cresap's forces did not encounter any Indian war parties but saw plenty of signs they were in the area. On the fifth day, May 28, 1756, the company split in two, 38 men going with Gist to Big Meadows, and 59 men going with Cresap, who went as far west as the Youghiogheny River. Growing weary, the men persuaded Cresap to turn back toward Savage River.

On May 28 at sunset, the incident that resulted in the naming of a mountain began. It started when Cresap heard an "Indian holler," and looking ahead, saw two Indians riding on horses toward him. Instead of taking cover, Col. Cresap marched toward them on the road, in his own words, "with my gun cocked on my shoulder." A "running fight" had begun.

Cresap temporarily lost sight of the Indians due to a bend in the road. About the same time the Indians came back into view, the black frontiersman suddenly appeared in support of Cresap. Standing on the road just 30 yards from Cresap, the brave black frontiersman "presented his gun" at the two Indians.

The Indians at this time "immediately alighted from their horses." Another Indian soon appeared, and the three Indians took cover behind trees, two on one side of the road and the other on the opposite side. Cresap and the black frontiersman were caught standing in the road without cover, "not having advantage of any trees at that place."

The courageous actions of the black frontiersman drew the attention of the Indians to himself and away from Cresap. Within seconds, "two of the Indians fired and shot the Negro," killing him. The bold behavior of the black frontiersmen allowed time for four of Cresap's men to return fire, killing one Indian, wounding another, and causing the other to flee.

The heroic sacrifice of the black frontiersman spared Col. Cresap's life. This allowed Col. Cresap to fulfill his destiny. Not too long after this incident, Cresap played a principal role in Western Maryland to help prepare the colony for events leading to the American Revolution.

John J. Jacob, a close friend of the Cresap family, embraced the legacy of the incident on the mountain in his biography, "Life of the Late Captain Michael Cresap," published in Cumberland in 1826. It is from this work that we know that the naming of Negro Mountain resulted from this incident.

Jacob wrote: "Cresap's party killed an Indian and the Indians killed the Negro, and it was this circumstance, namely: the death of this Negro, on this mountain, that has immortalized his name by fixing it on this ridge forever."

Nina Higgins, historian for the Cresap Society, contributed to this article.

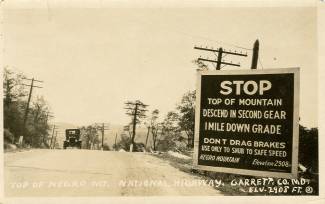

Photograph by C.E. Gerkins, Cumberland, Maryland. The postcard is from the collection of Albert and Angela Feldstein.

The article by Champ Zumbrun was published in the Cumberland Times News on March 10, 2008 and is used with permission.

A more detailed overview of the accounts surrounding the naming of Negro and other mountains in Western Maryland can be found in an article by Mary Meehan entitled, "Mountain Names in Western Maryland", Journal of the Alleghenies, Vol. XXXXI, 2005

Additional research on this subject by historian Champ Zumbrun indicates that Nemesis was a “free Negro,” and that the name "Nemesis" itself did not appear in writings until after over 120 years from the 1756 event on the mountain. Based upon even further research by Champ Zumbrun, the name “Negro Mountain” first appears on maps dating as far back as 1822. Additional maps bearing this name appeared in 1826, 1834, 1836, 1838, 1873 and 1876. The links are below.

Zumbrun’s research further states that John Jacob’s history of Michael Cresap published in 1826 confirms the mountain is named Negro Mountain as a result of the 1756 incident. Jacob had married the widow of Michael Cresap who was at the incident in 1756 that resulted in the naming of the mountain.

1822, Melish, John - Map of Pennsylvania : constructed from the county surveys authorized by the state and other original documents

1826, Melish, John - Map of Pennsylvania, constructed from the county surveys authorized by the State; and other original documents by John Melish

1836, Lucas, Fielding Jr - Maryland, Delaware, and Parts Of Pennsylvania & Virginia

1838, Bradford, Thomas G. - Maryland

1873, Gray, O.W. - Delaware and Maryland.

1876, Gray, Frank A. and Gray, O.W. - Maryland, Delaware and the District of Columbia.

And finally and perhaps most importantly, this research by Scott Williams:

“The oldest reference to the place name “Negro Mountain” was found in The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777. Nicholas Cresswell (1750–1804) was an Englishman from Derbyshire who left his farming community for the North American colonies at the age of 24. Cresswell was a diligent diarist and his notes on three years of travel in the Middle Atlantic colonies at the beginning of the Revolutionary War have provided a wealth of material for historians. His diary entries from April 1775 trace his travels from the Potomac Valley to the Ohio River including a recitation of each ridge that he crosses. In both his westward journey and his return to the Potomac Valley in October 1775 he cites 'Negro Mountain' as a landmark – an indication that the mountain was known by its current name just 19 years after the events of 1756. - The journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777

Negro Mountain also appears as a place name in a 1786 Bedford County property tax roll for Turkey Foot Township published in the Freeman Journal 6. The construction of the National Road on Negro Mountain is reflected in a table of distances published in the Maryland Gazette in 1807.”

Local historian Dave Williams also noted a reference to the ridge being known as "Negro Mountain" in an article, "A Quaker Pilgrimage; Being a Mission to the Indians from the Indian Committee of the Baltimore Yearly Meeting, to Fort Wayne, 1804"; William H. Love; Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 1, March 1909. pg. 5.