Collection Name

About

Senators: Local mountains need new names. Western Maryland representatives don’t support push to change Negro, Polish.

CUMBERLAND — Two local mountains need new names, a group of state senators say, and they want a commission created to select new monikers for Negro Mountain and Polish Mountain which “reflect more accurately the history and culture of the region within which they are located.”

None of the nine senators sponsoring Senate Joint Resolution 3 represent the region where the two mountains rise in the Allegheny Mountain range, with Negro Mountain in Garrett County reaching a height of 3,075 feet and Polish Mountain in Allegany County climbing to 1,783 feet from sea level.

The senate resolution isn’t too popular with the legislators who do represent those who live on and near the mountains.

“It’s just asinine,” said Delegate Kevin Kelly. Kelly wondered why Polish Mountain ended up in the resolution. “I’m of Irish descent. We’d love to have a mountain named after us. Let’s rename it Irish Mountain,” he quipped. State Sen. George Edwards and Delegate Wendell Beitzel joined in.

“I grew up on Negro Mountain and have a farm on Negro Mountain. I don’t know why people in the Baltimore area are so worried about it,” said Beitzel. The mountain, he said, was actually named in the language of the time in tribute to a black man’s heroism.

“It boils down to the political correctness stuff we’re into in this world,” said Edwards. “The name, at the time, was meant with honor and respect.” Edwards also said he doesn’t think Maryland has the authority to change the name of a mountain. The U.S. Board on Geographic Names of The National Geologic Survey has that authority and has previously rejected a name change, he said.

The history behind the names isn’t simple to pin down, especially in the case of Polish Mountain. It looks like the explanation Beitzel has heard about Negro Mountain is correct.

Champ Zumbrun, a retired forester who managed Green Ridge State Forest for many years, has researched local history and is working on a book on Maryland frontiersman Thomas Cresap. His coauthors include some of Cresap’s descendants. He’s found a letter Cresap sent to the Maryland Gazette in 1756, explaining the event which led to the naming of the mountain.

“The name honors one of our earliest black frontiersmen,” said Zumbrun. Cresap wrote that a free black man, who was a member of his volunteer rangers during the French and Indian War, acted heroically during a battle with Indians, and in fact saved Cresap’s life. The black frontiersman was mortally wounded in the battle and was buried on the mountain.

Another account provided by the Garrett County Historical Society largely agrees with that account.

“I suggest and recommend the name of Negro Mountain remain unchanged, as it is named in honor of a brave black frontiersman, one of the earliest “free” black frontiersman on record in American colonial history serving the cause of liberty against British tyranny, who saved on that mountain the life of Colonel Thomas Cresap, allowing the opportunity for Col. Thomas Cresap to contribute soon thereafter significantly to the American liberties we all enjoy today,” Zumbrun wrote in an email to the Times-News.

Zumbrun says a deed he’s seen from 1790 refers to “Polished Mountain,” but beyond that, Zumbrun has little evidence about the way the name developed, “things get changed over time,” he said. The rocks on the mountain tend to shine when wet, and the leaves of the Aspen trees which once covered the mountain can also be shiny, he said.

Kelly wondered why the senators backing the resolution wouldn’t want to rename organizations with seemingly politically incorrect, but historically significant names, like the NAACP or The United Negro College Fund, he said.

The resolution would require the governor to establish and appoint the members of the naming commission, who would be required to decide on new names by Dec. 31.

Sen. Joan Conway, one of the sponsors of the resolution, did not return a Friday phone call from the Times-News. Conway represents Baltimore.

For a complete article by Zumbrun on the naming of Negro Mountain, see Negro Mountain (The Naming 1)

Additional research on this subject by historian Champ Zumbrun indicates that Nemesis was a “free Negro,” and that the name "Nemesis" itself did not appear in writings until after over 120 years from the 1756 event on the mountain. Based upon even further research by Champ Zumbrun, the name “Negro Mountain” first appears on maps dating as far back as 1822. Additional maps bearing this name appeared in 1826, 1834, 1836, 1838, 1873 and 1876. The links are below.

Zumbrun’s research further states that John Jacob’s history of Michael Cresap published in 1826 confirms the mountain is named Negro Mountain as a result of the 1756 incident. Jacob had married the widow of Michael Cresap who was at the incident in 1756 that resulted in the naming of the mountain.

1822, Melish, John - Map of Pennsylvania : constructed from the county surveys authorized by the state and other original documents

1826, Melish, John - Map of Pennsylvania, constructed from the county surveys authorized by the State; and other original documents by John Melish

1836, Lucas, Fielding Jr - Maryland, Delaware, and Parts Of Pennsylvania & Virginia

1838, Bradford, Thomas G. - Maryland

1873, Gray, O.W. - Delaware and Maryland.

1876, Gray, Frank A. and Gray, O.W. - Maryland, Delaware and the District of Columbia.

And finally and perhaps most importantly, this research by Scott Williams:

“The oldest reference to the place name “Negro Mountain” was found in The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777. Nicholas Cresswell (1750–1804) was an Englishman from Derbyshire who left his farming community for the North American colonies at the age of 24. Cresswell was a diligent diarist and his notes on three years of travel in the Middle Atlantic colonies at the beginning of the Revolutionary War have provided a wealth of material for historians. His diary entries from April 1775 trace his travels from the Potomac Valley to the Ohio River including a recitation of each ridge that he crosses. In both his westward journey and his return to the Potomac Valley in October 1775 he cites 'Negro Mountain' as a landmark – an indication that the mountain was known by its current name just 19 years after the events of 1756. - The journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777

Negro Mountain also appears as a place name in a 1786 Bedford County property tax roll for Turkey Foot Township published in the Freeman Journal 6. The construction of the National Road on Negro Mountain is reflected in a table of distances published in the Maryland Gazette in 1807.”

Local historian Dave Williams also noted a reference to the ridge being known as "Negro Mountain" in an article, "A Quaker Pilgrimage; Being a Mission to the Indians from the Indian Committee of the Baltimore Yearly Meeting, to Fort Wayne, 1804"; William H. Love; Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 1, March 1909. pg. 5.

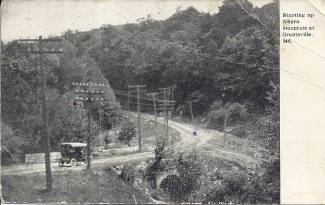

The postcard, from the collection of Albert and Angela Feldstein, was postmarked 8-11-1915.

See also Lawmakers clash over Western Md. mountain names, Herald-Mail, Feb 12, 2011, and also the Cumberland Times News article, 2/23/2011, attached here as a PDF.