Collection Name

About

History in black, white

Slavery and separation part of local heritage

By ANDREA ROWLAND

Blacks in Washington County share a local history rooted along a less than one-quarter mile stretch in downtown Hagerstown. Jonathan Street has housed, fed, entertained — and sometimes frightened — many of its black residents for more than two centuries.

Jonathan Street is so named only through the black district. The street is mostly white on each end, where it's known as Summit Avenue to the south and Forest Drive to the north. That is a point of contention among those who believe this makes it easy for the city to profile a Jonathan Street address as a black address.

The three predominantly black blocks sandwiched between Summit Avenue and Forest Drive once housed the county jail that held ne'er-do-wells and fugitive slaves waiting to be freed, reclaimed or sold on the nearby auction block. Jonathan Street was a settling place for free blacks in the county and the site of their first churches, city homes and businesses.

Until the 1960s, common practice prevented members of Hagerstown's black community from leaving Jonathan Street.

Black history files at the Washington County Historical Society include a recent comprehensive study of the area called the "Heritage Preservation Project." The study includes census data and historical, social, educational, religious, economic and architectural information about the area's first black community.

The City of Hagerstown in 2002 commissioned the study to help preserve an often overlooked slice of county history, City Planning Director Kathleen Maher said. Local black history most likely dates to the mid-1700s, when European American settlers brought their slaves to Washington County. By 1790, Washington County's nearly 16,000 residents included 64 free blacks and almost 1,300 slaves — half the number of enslaved persons in neighboring Frederick County — while the state's slave population totaled about 103,000, according to the first American census.

Washington County landowner John Barnes in 1790 boasted the highest number of slaves at 75. The county's slave and white populations continued to climb in tandem into the first quarter of the 18th century, peaking at more than 3,200 slaves in 1820, but whites in Washington County still ranked low statewide in slave ownership.

Prince George's and Anne Arundel counties each counted more than 10,000 slaves, according to 1820 census figures.

Only about 11 percent of white Washington Countians could afford to own slaves, according to the "Heritage Preservation Project." The area's large German population tended to avoid slave ownership, and a great number of slaves weren't needed to work on the county's proliferation of small, owner-occupied farms.

Quakers and Methodists led anti-slavery movements in Washington County, but the area was far from a safe haven for escaping slaves. The county's border state location attracted slaves fleeing to the north through neighboring Pennsylvania's many Underground Railroad stops.

Although there are no documented Underground Railroad stops in Washington County, "Big Sam" Williams, a free black who owned a farm on the Potomac River at Four Locks, was known for helping escaping slaves across the waterway in the mid-19th century. (Williams' son, Nathan, and his family farmed Fort Frederick — now a state park — from 1857 to 1911.)

Washington County's roads were patrolled for escaping slaves, and blacks caught without documentation were held at the county jail on Jonathan Street until their status was resolved. Racial constraints

Racial constraints tightened after a Virginia slave rebellion in 1831. The Maryland General Assembly passed legislation that reduced blacks' access to religion, education and jobs. Black farmers needed special licenses to sell their goods, and free blacks were discouraged from returning to the state, according to information at the Washington County Historical Society.

Maryland even dedicated state funds to return free blacks to Africa. In 1833 19 free blacks from Frederick and Washington counties were sent to Liberia.

In Hagerstown, blacks were not allowed to gather in such public places as the Market House. As a gateway to the North, Hagerstown beckoned slave catchers and traders. Slave markets were found in Sharpsburg and Beaver Creek, on Jonathan Street and in front of the court-house in Hagerstown.

The possibility of being shipped to the South's brutal cotton fields so terrified some local slaves they mutilated themselves to discourage buyers. The fear of going south prompted a slave woman owned by Susan Gray of Boonsboro to cut off her left hand with an ax in 1906, according to historical documents.

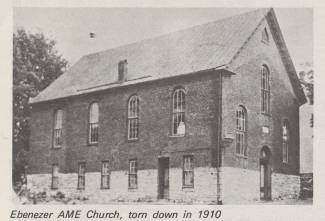

Two black churches were established on and near Jonathan Street — Asbury United Methodist Church in 1818 and Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal in 1838 — as free blacks continued to settle in the area. The county's black population of about 4,130 included more than 1,500 freedmen by 1840, according to census data.

The number of free blacks had increased to 1,826 by 1850, while the number of slaves in the county dropped from 2,546 in 1840 to 2,090 in 1850. Many local slave owners freed their slaves in the decade leading up to the American Civil War. The 1860 census counted 1,435 slaves in the county and nearly 500 free blacks — including 31 property owners — living in the Jonathan Street community.

'Colored units'

The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 allowed blacks to serve in U.S. Army "colored units." Seventeen black men from Washington County enlisted in the Union Army, including members of Hagerstown's Moxley Band, according to a book by the late Marguerite Doleman of Hagerstown.

Formed by Robert Moxley in 1854, the band's 12 enslaved musicians played at public events until they joined the First Brigade of the U.S. Colored Troops. The band was used in part to recruit other slaves in the region for military service.

The end of the war found free blacks trying to find housing and competing for work in Washington County. Many moved to urban areas where jobs were more plentiful, while some ex-slaves stayed on county farms as hired help and tenants, the study says.

The Freedmen's Bureau, which was created by the U.S. War Department in 1863 to provide blacks with living assistance and support, started the county's first school for black children in 1869. By 1870, black communities had formed in Williamsport, Clear Spring, Sharpsburg, Sandy Hook, Hancock and Beaver Creek — but Jonathan Street remained the base for nearly 900 of the 2,826 blacks in the county, according to census data.

The addition and improvement of railroad lines through Washington County turned Hagerstown into the Hub City in the 1870s and 1880s. The local manufacturing industry boomed, but few blacks benefited from the economic upturn.

Barred from working in factories with whites, blacks took low- paying service jobs at restaurants, hotels, barbershops and in the large new homes on Potomac Street. Black railroad workers were limited to picking up coal along the tracks or serving as janitors, the heritage study says.

Blacks couldn't use the county hospital or Hagerstown YMCA, shop in the city's central business district or attend the theater with their white neighbors and employers.

This was the environment to which Buffalo Soldier William O. Wilson returned in 1893 after earning the Medal of Honor for bravery during the Indian Wars of the late 1800s. It would be nearly a century before his achievement was recognized with a local memorial.

Middle class

A black middle class formed on Jonathan Street despite — or perhaps because of — the countless racial barriers. Residents opened businesses to serve their own community.

Walter Harmon's black hotel was a notable addition to the community because visiting blacks weren't allowed to lodge in white hotels, the heritage study says.

Nearly 20 of the black men who were barred from holding local office or working as police enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War I, and 200 local blacks served in World War II. A new high school was built on North Street after that war, enabling local black students to attend 12 years of school for the first time.

The City of Hagerstown in the 1950s and 1960s built two housing projects — Bethel Gardens and Douglas Court — for the Jonathan Street community. Civil rights legislation then opened Jonathan Street's exit door, but many chose to stay.

The photograph of Ebenezer A.M.E. Church in Hagerstown is from We the blacks of Washington County, by Marguerite Doleman, 1976. The Church was founded in 1838.

The text is reprinted with permission by The Herald-Mail Co. of Hagerstown, Md

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (the Freedmen's Bureau) was started in 1865. see The Freedmen's Bureau, 1865-1872, National Archives.

Thomas John Chew Williams in his History of Washington County documents the events of Susan Gray's slave:

The only thing the negroes stood in mortal terror of was being sold to the Cotton fields. A threat of such a sale always produced results. One unmanageable negro girl about 20 years of age, the property of Mrs. Susan Gray, of Boonsboro’, had been threatened with a sale, and seeing some visitors come to the house whom she mistook for negro buyers, she deliberately took an axe and cut off her left hand so as to make herself unmarketable. A man confined in jail cut off four of his fingers to prevent the sale, and another with a similar motive broke his skull with a stone" (page 251).

The Herald of Freedom and Torch Light carried the story 6 May 1857