Collection Name

About

Hancock to Green Spring depot - Ted Alexander

When the fighting started in the streets of Hancock, McCausland withdrew westward on the "National Pike" toward Cumberland. This prominent western Maryland city was a tempting target for the Confederates. There the National Road moved west into Pennsylvania and Ohio and the C & O Canal reached its western terminus. Cumberland's most strategic feature, however, was the B & O Railroad's repair shops and hundreds of pieces of rolling stock. If McCausland could take Cumberland, he would fulfill to a degree Robert E. Lee's goal of disrupting delivery of coal to eastern cities. Not only could coal mines in the Cumberland area be destroyed or closed, but valuable coal shipments from western Maryland also could be stopped. As a result, the cold and war-weary people of the North would be given one more reason to want a speedy end to the conflict. Perhaps because the Lincoln government had failed to take adequate steps to protect the border, Northerners would be persuaded to vote for his Democratic opponent, George B. McClellan, in the upcoming presidential race.

In command of Federal forces at Cumberland was Brigadier General Benjamin F. Kelley. Although a native of New Hampshire, he had moved to Wheeling in 1851 at the age of nineteen and became a B & O freight agent. In 1861, Kelley was severely wounded at the battle of Philippi, leading the 1st West Virginia, a ninety-day regiment he had raised. After his recovery, he was commissioned a brigadier general. From summer 1861 through June 1863, he commanded forces at the brigade level and higher that were responsible for protecting the B & 0 Railroad and containing the Confederate threat in West Virginia and along the upper Potomac.

On June 24, 1863, the Union Department of West Virginia was created by subdividing the Middle Department and General Kelley took over as its first commander. In the spring of 1864 Kelley was replaced as departmental commander by Major General Franz Sigel. Now, in August, 1864, he found himself the commander of the Reserve Division of the Department. Kelley had nearly 3,000 men, including artillery, cavalry, and infantry, at his disposal, but this was not nearly enough, for his orders were not only to guard Cumberland but also the railroad and entire region from Sleepy Creek to the Ohio River. Also, three regiments, the 152nd, 153rd and 156th Ohio were 100-day units about to muster out. 1

For a week, Benjamin Kelley had begged Washington for assistance. Indeed, when Crook withdrew to the Potomac on July 25, the frantic and isolated Kelly correctly anticipated a Rebel strike at Cumberland to "destroy the railroad and canal and public stores." Realizing he could expect little support from Hunter's beleaguered forces to the east, he had asked in one dispatch to Washington whether reinforcements might be sent from Ohio or Indiana. He also requested assistance from the B & O president, John W. Garrett, to assist him in removing public property and railroad equipment "to a place of safety." 2

. In obedience to orders received from Major General Henry Halleck on July 31, General Kelley sent out details that evening to block the roads leading from Hancock to Cumberland by felling trees and destroying bridges. He also ordered his outposts near Hancock to fall back to Cumberland. The city itself was panic stricken. Rumor had spread that Confederates were advancing from both Hancock and Bedford. On Sunday night (July 31) Cumberland's Mayor Ohr addressed a public meeting at the market house, urging the formation of a militia to assist General Kelley in the city's defense. Three companies of citizen soldiers were formed, numbering about 200 men and commanded by militia General C. M. Thruston. This probably boosted local morale, but these "minute men," indifferently armed, would be little match for McCausland's veterans. 3

While the Yankees prepared for the worst, McCausland's long column, encumbered with wagons full of booty taken from the various towns they had visited, pushed on toward Cumberland. Along the way the Confederates also felled trees and burned bridges behind them to prevent an effective pursuit by Averell's cavalry. By now the Union cavalry had been without rations for two days, and as Averell explained in a dispatch to General Kelley, "My horses are used up." 4

Around 3:00 a.m. August 1, the Confederate column halted at Bevansville, atop Polish Mountain, to rest both man and beast and to cook and eat rations. At sunrise they continued the march with McCausland's brigade in advance. That morning, Kelley sent his son, Lt. Tappan W. Kelley, with a squad of Ohio cavalry (probably about 28 men) eastward on the Baltimore Road to monitor the Confederate advance and retard it in order to buy time to set up his defenses. By noon the raiders were reported to be just 12 miles from the city, near Flintstone, where they exchanged fire with elements of the 11th West Virginia Infantry. 5

Because of this imminent threat, Kelley prepared for battle. He had at his disposal the following units: Company E, 6th West Virginia; Companies A, E, F, and H, 11th West Virginia; 152nd Ohio; 153rd Ohio; 156th Ohio; 3rd Independent Company, Ohio Cavalry; One section (three 3 inch ordnance rifled cannon) of Battery B, 1st Maryland Light Artillery (Snow's Battery); and two sections (six brass, rifled 12 powder howitzers) of Battery L, 1st Illinois Light Artillery. In addition to these units, Kelley reported having "several hundred stragglers, mostly unarmed, who had stampeded from the front after the battle near Winchester, July 24” together with the hastily armed local citizens. The 153rd Ohio was sent to Old Town to block the ford across the Potomac in case McCausland attempted to withdraw into Virginia at that point. Altogether the Union troops defending Cumberland probably numbered about 2,500, a large percentage of whom were 100-day troops, stragglers and citizens. Kelley did possess a superiority in artillery, nine guns to McCausland1s four, plus good defensive positions. 6

Upon learning of McCausland1s advance, Kelley immediately posted the 156th Ohio (856 men), the available companies of the 11th West Virginia, and his artillery to Evitts Creek Valley, about 2-1/2 miles east of Cumberland. Here the Yankees dug trenches and were well concealed by timber on high ground overlooking the Baltimore Pike and a mill owned by John Folcks, known alternately as Pleasant Mill or Folcks’ Mill. The balance of the Federal forces held the fortifications closer to the city. While the merchants of Cumberland were busy loading their goods to send to safety and B & 0 trains likewise headed west for the same reason, thousands of curious citizens lined the hilltops to watch the expected battle.

At approximately 3:00 p.m., several companies from McCausland1s brigade advanced across the Evitts Creek bridge within range of Federal small arms fire. At this point, the Federals opened up with both musket and artillery fire, forcing the surprised Confederates to seek cover behind the bridge, mill, house, barn, cooper's shop and other outbuildings. From here rebel "sharpshooters" opened a "galling fire" upon the enemy artillery. This fire, in turn, was neutralized by Federal skirmishers.

Recovering from this concealed hostile fire, the Confederate advance force regrouped and formed a skirmish line. McCausland, meanwhile, deployed his four guns on a hill about 700 yards behind his skirmishers. Although his skirmishers would threaten Kelley's left flank, the Federal position was too strong for this movement to make a difference. The fighting continued throughout the afternoon but as darkness neared, McCausland, sitting near the guns in consultation with Johnson, decided that further attempts to take Cumberland would be futile. Confederate casualties had mounted to eight killed and over 30 wounded, while the Union loss was only one killed and four wounded. 7

The question facing the Southern commander now was how to get his raiders safely across the Potomac into Virginia. Not sure of the strength of the force he was facing and equally uncertain of Averell's disposition behind him, "Tiger John" now needed to find a way out, lest he get crushed between two enemy forces. Enter Harry Gilmor. McCausland asked the chivalrous major if he knew the country well. "No, sir, I was never here before," replied Gilmor. "Have you no guides?" asked the general, to which Gilmor replied, "I had two, but both got drunk and went off." McCausland then proceeded to impress upon the Major the necessity of getting safely across the Potomac post haste. The Marylander replied that if so desired, he would take his command and make a reconnaissance. Gilmor stated in his memoirs that he led his men out at 4:00 p.m. After going less than a half mile, he "obtained from a citizen all I wished to know" and after passing this on to General McCausland, seized a local Unionist and at gunpoint forced the man to lead him to Old Town. After going about two miles, he sent a courier back to inform McCausland of the condition of the road and left pickets at intersecting roads to guard the Confederate flank. This obscure route, known as Hinkle Road, led up the side of a mountain as it wound toward Old Town. Gilmor had not gone more than three miles when night fell. His trusty Unionist guide, however, with the cocked revolver at his head "knew the country well and made no mistake." 8

Back at Folcks' Mill the Confederates started withdrawing around 11:00 p.m., with Johnson's brigade in the lead. The Southerners left behind more than 30 dead and wounded, two artillery caissons, several carriages and a large quantity of ammunition. They also kept campfires burning to deceive the enemy. 9

At approximately 1:00 a.m., Gilmor’s reconnaissance force was within a mile and a half of the river. After exchanging shots with a Union picket post (21 men from the 6th West Virginia Cavalry) the major wisely decided it would be safer not to continue into the darkness. Therefore, Gilmor led his men into a woods to bivouac until daylight, planted an ambush for any enemy that might approach, sent scouts to explore the ford and sent a courier to tell Johnson to hurry up.

At dawn, Gilmor's scouts reported that the river ford was held by a strong Federal force. This was the 153rd Ohio National Guard commanded by Colonel Israel Stough, a 100-day unit numbering more than 700 men and due to muster out in a few days. When a courier arrived stating that Johnson was on his way. Major Gilmor himself led another reconnaissance. Upon reaching the C & 0 Canal about a mile above Oldtown, he found the Federals had burned the small bridge that crossed the canal there. This did not worry Gilmor because he knew there was a more substantial bridge directly opposite the ford at Oldtown. As his reconnaissance force moved through a heavy morning fog, the advance, under Lt. William H. Kemp of the 2nd Maryland Cavalry, ran into a Union ambush that inflicted casualties of one killed and two wounded. This caused Gilmor to halt his force, dismount and wait for Johnson's arrival.

The fog was starting to lift when Johnson arrived and Union soldiers could be seen dismantling the bridge across the canal at Oldtown. Meanwhile, Stough had concealed most of his Ohio regiment on wooded hills between the canal and the Potomac. What followed was one of the most unusual engagements of the Civil War. At a little after 5:00 a.m., Johnson led the 27th Virginia Cavalry Battalion and 8th Virginia Cavalry to attack the Federal front, while the dismounted 21st Virginia Cavalry, 36th and 37th Battalions, led by Colonel Peters, quickly built a bridge across the canal and struck both flanks of the Union line. At the same time two Confederate field pieces supported the assault. The Yankees fired a volley at about 300 yards that passed harmlessly over the Confederates, hitting just two or three of their horses, and then fled across the ford to Green Spring Station on the Virginia shore. 11

There about 100 men took refuge in a well constructed blockhouse about 100 yards from the river while the rest took position behind a railroad embankment on high ground just opposite the Potomac At this point in the battle, a train came into sight on the B & 0 tracks, causing the Confederates some puzzlement. One soldier recalled that "it was an odd looking train and set the boys to guessing, as no troops were in sight." This was the same "iron-clad" train that had given the Confederates hell at Hancock. Now the "iron clad" with the locomotive in the center and three rifled cannon in each end car was on the Virginia side of the river in front of them. The middle cars contained Company K, 2nd Maryland Potomac Home Brigade, commanded by Captain Peter B. Petrie (3 officers and 64 men). These troops were able to fire from numerous holes constructed for that purpose. 12

Next, the Southerners attempted to take the Union positions by a direct frontal assault. The dismounted 8th Virginia and Gilmor's 2nd Maryland, which was mounted, rushed the ford and made it to the Virginia shore under a heavy storm of artillery and rifle fire. They found themselves pinned down, however, the dismounted men lying on the edge of the water and the mounted Marylanders "under the Virginia shore, in water knee deep." The Confederates tried to support this attack with artillery but heavy timber along the river protected the Union blockhouse from the percussion shells lobbed by the Southern batteries.

Having lost about a dozen men killed and wounded and realizing his position was untenable, Gilmor rode to the rear, where he found McCausland and Johnson in consultation. There he argued for closer artillery support, lest the raiders stay trapped at Oldtown, while Yankee reinforcements were brought up. Acknowledging the truth of his remarks, the generals doubted whether a battery could be moved up closer because of the deadly fire coming from the "iron clad." Leaving his superiors in their deliberation, Gilmor rode into Oldtown to persuade Lt. John McNulty to attempt the desperate mission. According to Gilmor, McNulty was "ready for anything. Accordingly, we took two pieces down to the bridge, crossed it at a gallop; had two horses killed, which we dragged along dead in their harness; got a position on the ridge, unlimbered the pieces, already shotted and primed." Although under heavy fire from the Union "iron clad," McNulty’s best gunner, Corporal George McElwee, coolly sighted in and fired upon the iron monster. When the smoke cleared, the locomotive was enveloped in a cloud of steam. McElwee’s shot, perhaps the most accurate or luckiest of the war, had pierced the boiler, blowing it up and stepping the train. His next shot was equally as effective, entering a porthole, and exploding, dismantling a gun and killing three Federals. Two more shells hit the cars containing the infantry, causing the Maryland Unionists to leave the cars and flee to the woods. Seeing the "iron clad" disabled, the Ohio troops behind the railroad embankment fled too, leaving Stough and his troops in the block house to fend for themselves.

Even though the Federals in the blockhouse were outnumbered, their position was formidable. Gilmor recalled that it "was a new block-house, built in the most approved style with bomb proof . . . ." Indeed, he described it as a greater obstacle than the "iron-clad" because the troops inside it had a clear field of fire but could not be seen from the Maryland side of the river. McNulty's artillery fired 50 rounds "feeling for it," and only one met its mark. When one of Johnson's regiments (possibly the 8th Virginia) charged up the bank onto the Union fortification, it was repulsed with heavy casualties. For an hour and a half the Confederates were pinned down under the Virginia shore, "and if any one shaved his head above the bank a bullet was sure to whistle very near it." 15

Finally McCausland decided to make a frontal assault using the 8th and 21st Virginia. To support them, one gun of the Baltimore Light Artillery moved to the river under heavy fire, unlimbered in the river and prolonged by hand to the Virginia shore. As the attack was ready to begin, McCausland reversed his decision opting instead to demand the immediate surrender of the blockhouse under the threat of no quarter when the place was taken. Two members of the 2nd Maryland were sent forward under a white flag with the terms of surrender. After a brief discussion. Colonel Stough agreed to surrender under the following terms: (1) that his men be immediately paroled; (2) that private property be respected; (3) that men should be allowed to retain their canteens, haversacks, blankets, and rations and (4) that he be allowed to use a hand car to transport his wounded back to Cumberland.

Inasmuch as trying to take the blockhouse by force would cost the Confederates heavily in casualties and time, McCausland readily approved the terms. The Union commander and his force of 80 men marched out, of the blockhouse, stacked arms, and took their parole. While this transpired, Stough was very vocal in his disgust for the men who had deserted him. The fight at Old Town or Green Spring Depot had been a onesided affair as far as casualties go. Indeed, throughout this raid, on the road to Mercersburg and Chambersburg, at Folcks1 Mill and now here, McCausland had faced unexpected resistance that drained his manpower. The Union after-action report lists Confederate casualties at 20 25 killed and 40 50 wounded as opposed to Federal losses of 2 killed and 3 wounded. Neither McCausland nor Johnson listed their casualties in any reports, but Gilmor mentioned that "about a dozen men" had been lost prior to the hit on the "iron clad" and that the assault on the blockhouse cost the Rebels "severely in officers and men." After destroying the blockhouse, "iron-clad" cars and a section of track, McCausland's force, "rejoicing and feeling somewhat relieved," marched 9 miles to Springfield, West Virginia, where they camped along the South Branch of the Potomac through August 3rd. Here men and horses rested and the wagon loads of booty taken during the raid, along with dismounted men and crippled horses, were sent bade to the Shenandoah Valley.

The text is from Alexander, Ted. "McCausland's raid and the burning of Chambersburg." Thesis, University of Maryland, 1988

This section is from a chapter entitled - "Hancock to Moorefield".

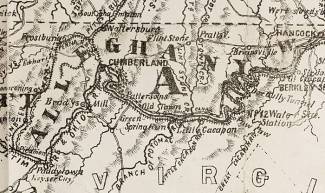

The map is a section of New map of Maryland, Baltimore: John F. Weishampel, 1875