Collection Name

About

Construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal began in 1828 and the canal opened new sections as it reached a dam and the feeder lock behind it that could provide water to the section of canal below. The first 22 miles between Georgetown and Dam 2 near Seneca opened in 1831, followed by the section to Dam 3 above Harpers Ferry in 1833; to Dam 5 above Williamsport in 1835, to Dam 6 above Hancock in 1839, and finally to Dam 8 at Cumberland in 1850.

The 184.5 mile canal climbs the 608 feet from tidewater at Georgetown to Cumberland by means of 74 lift locks. Along the way eleven aqueducts carry the canal over major Potomac tributaries and more than 200 culverts carry smaller streams under the canal. Deep in the mountains a 3118 ft. tunnel through a ridge avoids a double-lobbed-bend of the Potomac that would have added five additional miles.

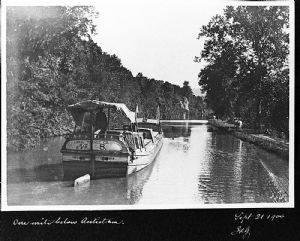

The eastern terminus at the port of Georgetown and the western basins at Cumberland, as well as Williamsport at mile 100, constituted the canal’s three major ports. Smaller wharfs and basins served local communities up and down the canal, such as O’Briens Basin near Antietam Village.

Three river locks were built to allow boats to pass between the canal and Potomac River. The first, just below Edwards Ferry, served boats crossing the river from northern Virginia landings near Leesburg. At Harpers Ferry a second river lock served boats coming down the Shenandoah. A third river lock across from Shepherdstown, facilitated the shipping of hydraulic cement from the Boteler mill below the town, as well as agricultural and other products shipped from Shepherdstown’s wharfs.

Upstream from Dams 4 and 5 the canal was interrupted by rocky ridges rising steeply from the river. To avoid the expense of blasting through them, the canal was discontinued and locks allowed boats to enter the slackwater pools behind the dams. A narrow towpath along the river’s edge was created for the mules. Dam 4’s “Big Slackwater” section was 3½ miles long, while “Little Slackwater,” above Dam 5 was a mere half a mile long.

Navigating in the slackwater sections was more hazardous than in the canal, and one of the many fatal accidents that occurred in C&O Canal history took place on May 1, 1903 when Captain Kime’s boat lost its towline and was swept over the dam. The captain was fatally injured and a young daughter drowned, but Mrs. Kime, another daughter, and a friend boating with them, all survived, although with significant injuries.

Between Dam 6, ten miles above Hancock, and Cumberland’s Dam 8 at mile 184.5, are fifty mountainous miles where construction came to a virtual halt for several years in the early 1840s. As a result it was not until October 10, 1850, that the canal finally opened from Dam 8 at the Cumberland terminus. By then it was generally accepted that the canal would go no farther despite, the original plan to reach the Ohio River.

Once the canal opened to Cumberland, coal rapidly became the primary cargo with shipments reaching between 797,000 and 905,000 tons a year during the canal’s most prosperous years of 1870 to 1875. Not until the third quarter of the 19th century did railroad technology reach a point where it could compete with canals in the transportation of heavy freight (although railroads had rapidly proved superior for the transportation of passengers and lighter cargo, such as agricultural produce).

During the construction years numerous misfortunes slowed the canal’s progress and increased costs, including epidemics of diseases such as Asiatic cholera, labor unrest and shortages, and national economic downturns. But chief among the canal company’s difficulties, continuing throughout its history, was the damage done by periodic floods—or freshets as they were then known. Among the worst were those of June 1836, September 1843, October 1847, April 1852, November 1877, June 1889, and March 1894.

During the Civil War the canal served to transport military supplies and personnel and was important to the provision of coal and agricultural products for the federal government and the District cities of Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria. The canal’s direct route to the tidewater port of Georgetown was an advantage not possessed by the B&O whose mainline ran north and east from Point of Rocks to Frederick and Baltimore. Not until 1873 would the B&O open its Metropolitan line directly into the Federal District, although it still lacked access to the industries and wharfs at Georgetown.

On June 1–2, 1889, a flood that eclipsed all previous recorded floods in the Potomac Valley did devastating damage to the canal, as well as other transportation routes, bridges, businesses, and homes near the Potomac and many of its tributaries. Already deeply in debt, the C&O Canal Company had no choice but to declare bankruptcy. On March 3, 1890 the court appointed receivers under the mortgage of 1844 to restore and operate the canal. The canal reopened in September, 1891, and was operated under the receivership until the flood of 1924 when the court gave permission to discontinue operation following damage by yet another flood.

In 1938 the canal was sold to the government by the B&O Railroad whose ownership was based on their holdings of the 1844 bonds that mortgaged the canal property and repair bonds of 1878. In 1971, after a long struggle on the part of a diverse constituency, the C&O Canal became the C&O Canal National Historical Park.

Throughout its 22 years of construction and nearly a century of operation, the canal was home to countless men, women, and children who worked at locks or on boats. In addition it employed a wide variety of craftsmen, laborers, engineers, and administrative or supervisory personnel. In addition to its heavy use by the large coal companies, it was relied on by farmers, businesses, and individuals to transport goods in both directions, ranging from fertilizer from South America to salted and pickled seafood and fish from the tidewater.

It would be hard to overestimate the diverse cultural and economic contributions of the canal to the region’s history and heritage or its value today as an extensive and unique recreational and environmental resource.