Collection Name

About

MARYLAND CONSERVATIONIST

PUBLISHED BY THE MARYLAND GAME AND INLAND FISH COMMISSION • $1.00 PER YEAR

March 1954

LET’S SAVE THE C AND O CANAL —A LITTLE JAUNT

From White’s Ferry, Md. to Shepherdstown, W. Va., Tells the Story

The friendly “Whistle Stop” restaurant at Brunswick, Maryland, will linger in our memory; greetings we received at Shepherdstown, West Virginia—“Oh, you are cave men!”—will definitely not be forgotten. These are but a couple of the highlights in a two-day, 38 mile hike which George, my 14byear old son, and I made a couple of weeks ago along the towpath of the C & O Canal, starting at White’s Ferry, Maryland, and ending at Shepherdstown, W. Va. We were hiking for the fun of it, but also had a mission. Our dreams envisioned nothing less than to help save the C & O Canal from bureaucracy and determined roadbuilders.

Some years had passed since I was last on the C & O Canal at White’s Ferry; and nearly three decades since I fished at this point, about the time barge operation ended in 1924. I had never before followed the canal mile by mile or lock by lock. We wondered what we would find. I shared my young companion’s thrill of exploration and adventure. He shared with me the serious side of our trip. What would we find to justify preserving these last few acres of relatively unspoiled nature existing anywhere within 100 miles of Washington? What would we see that would challenge the roadbuilders who want to level the canal and towpath, slash away the trees, forever and for all time destroy the spell of peace and quiet we enjoyed so deeply this first Sunday morning? Could some small section in the East—at the seat of Government — receive protection like that afforded vast park and forest areas of the West? Must the average citizen of moderate means “go west” to see an untrammeled acre of God’s creation? These and many similar question we asked, and answered, on this short but fun-packed jaunt.

Nature herself, we soon learned, pleads our cause for us with an eloquence we could not hope to match. Canal and towpath are now part of the natural scene, as though built there by the hand of time. Three decades have integrated towpath and canal with earth, rocks and trees; with massive palisades above, the Potomac running swiftly just below.

A road on the bed of the canal, we could see, would very nearly destroy all of this. A road, however carefully built, would soon necessitate destruction of the sturdy old masonry viaducts and underpasses — which the roadbuilders claim they would preserve. While mostly in perfect preservation, they are too narrow or too weak for modern transport. Too narrow for clear and safe passage of vehicles guided by impatient drivers.

And why build a road when the area, either for pleasure or transport, is already well served with roads? We found this to be the fact—contrary to the findings of these modern "highwaymen!" Numerous access roads, we found, touch the canal at convenient intervals, almost as tho deliberately placed and spaced to serve the old canal in multiple use as a nature sanctuary and outdoor recreation area.

Harpers Ferry is a ghost town. Some people “collect” them, as in Nevada. The old Opera House, the site of the old arsenal—scene of John Brown’s Raid—the scenery where Shenandoah and Potomac meet in a cleft of mountains, suggest that one of a series of hostelries of the future, from Washington to Cumberland, would surely be established here. Why, we thought, cannot this great nation of ours, at its Capital City, afford to preserve the outdoor activities along a canalway and trail-way, supported by hostelries and meeting places so familiar to New England and in other lands?

Areas along the canal are already being developed for recreational purposes on a local basis. We found many boat and canoe parks, baseball and recreation fields, fishing camps, camping and boy scout areas, and guest cottages. Other areas—large areas—are wild, unspoiled. Truly a bit of God’s creation—a cathedral of Nature where those who love wild, unspoiled forest may go to enjoy it and refresh their souls. Here the naturalist may find his haven—as wildlife finds it sanctuary.

On broad stretches of the Potomac above Harpers Ferry duck blinds and large flocks of mallards and black ducks were in evidence —and hunters stalked them. Hunting in some areas, as well as fishing, can be preserved. The roadbuilders would destroy most of it. The old masonry aqueduct crossing of the Monocacy—finished in 1833 and in almost perfect condition— may be reached just beyond the little village of Dickerson, Maryland. Sugarloaf Mountain, familiar scene just north of the Monocacy crossing, like so many other points along the way, is steeped in history. We felt the movement of armies as we crossed Antietam Creek, scene of the bloodiest battle in the War Between the States.

The canal cost $27,000,000. Those were the days when the dollar was worth 100 cents, and maybe more. Why, we kept repeating, throw away this man-made investment? But no amount of dollars, we estimated, could possibly buy or re-establish the values we found at every hand. Nature’s loving gift of beauty marred or gone forever! History scuttled for a road! The quiet woods were a good place to ask about the economy of doing away with all of this investment and all of these values. For what? A road not needed because it already exists in just the right proportions and locations. Where did this road economy come from? We could only guess. Some few additional access roads could and should be added.

Our first day’s journey brought us to Brunswick, Md., railroad town and main switching point of the B & O. The “Whistle Stop” is the meeting place of these railroad folk, and if you talk with them chances are someone will invite you to watch the wizardry of the switching operation controlled from a high tower by one man. Or maybe he will give you the lowdown on shooting woodchucks, just as Mr. R. T. Foster, retired railroader, did for us. We figured we could have made Harpers Ferry— 26 miles for the first day—if we had brought along our ice-skates, as much of the canal, partially filled with water, was frozen solidly. In the future it would be perfectly feasible to ice-skate as to cycle or canoe, or ride horseback, all the way to Cumberland.

We reached Shepherdstown a bit after dark the second day and enquired at the first home we came to about a place to stop. Young John Lucas, son of local banker, Brooks Lucas, asked if we were “cave men”. This was our introduction to the science of speleology, or cave exploration. It seems that the reputation of Dr. Hal Wagner, Shepherdstown physician, as a member of the D. C. Grotto Society and the National Speleological Society is well known, and to young John Lucas, anyone who approaches Shepherdstown looking like we did, particularly if a member of the party limps a bit, has just emerged from a cave. Dr. Wagner taped up my bum left knee.

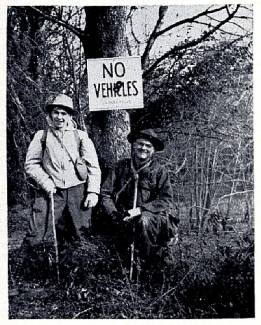

John Lucas showed us his extremely rare and valuable collection of Indian tomahawks and arrow points, and Civil War relics from Antietam battlefield. His collection included one of the rare pre-Civil War muskets manufactured at the old Harpers Ferry arsenal. Museum pieces all of them. The pay-off highlight of our trip came as we sighted the marker. “No Vehicles Allowed”, posted by the National Park Services on the edge of the old towpath. This we took to be a goodly omen for the future.

John Claggett, a DC lawyer, made this trip before the more well-known Justice Douglas walk. When he walked is unstated; the article was published in March 1954.