History of Antietam National Cemetery :including a descriptive list of all the loyal soldiers buried therein together with the ceremonies and address on the occasion of the dedication of the grounds, September, 17th, 1867 was published in 1869. It lists those Union soldiers buried in the Antietam National Cemetery in Sharpsburg, Maryland, as of 1867. Many died at the nearby Battle of Antietam and the fighting on South Mountain in September 1862. In addition, Union soldiers who died in Allegany and Frederick counties and elsewhere in Washington County, Maryland, are interred here too. The battle of Monocacy in Frederick County in July 1864 produced large numbers of dead. Other skirmishes in the state at Funkstown, Hagerstown, Boonsboro, Folck’s Mill, Weverton, and several other small towns also produced casualties, many of whom are buried in Sharpsburg. Some of those Union soldiers injured in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia were transported to Maryland hospitals and if they died were buried in the Antietam National Cemetery.

Those who did not die on the battlefields often died later in hospitals from their injuries or from illnesses. Homes, barns or churches close to the battlefields, like Smoketown and Locust Spring / Big Spring near the Antietam battlefield, were pressed into service. After the battle about seventy-five field hospitals were established in the surrounding area. The Smoketown Hospital, for example, was described as a collection of 80 tents, an oak grove and two dilapidated cabins. When Dr W. R. Mosley, Assistant Medical Inspector, visited the hospital in November 1862 there were 479 patients under treatment, 232 were wounded soldiers, 237 were sick. Typhoid fever, dysentery and diarrhea were the most prevalent illnesses (John Nelson).

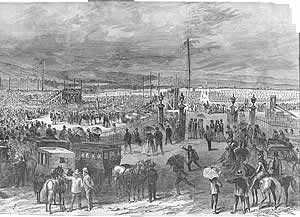

The hospitals in Clarysville, Cumberland, and Frederick were not close to the large battles, but were places to which the injured and sick were transported. The Clarysville Hospital, west of Cumberland, which this text lists as the origin of 177 bodies interred in the Antietam National Cemetery, is a case in point. It was established in the Clarysville Inn in 1862 to relieve the conditions of those in the hospitals in Cumberland, and between 1862 to 1865 at least 1,000 to 1,500 soldiers were hospitalized there at most times and probably as many as 2,000 at some times. The injured were transported from battles in Virginia – Winchester, Cedar Creek, New Market and others. Those Union soldiers who died in Clarysville were either collected by relatives or buried in the hospital cemetery, to be later re-interred at Antietam (Harold Scott).

Gerald Linderman reports that twice as many soldiers on both sides of the conflict died of disease as were killed in combat or mortally wounded. Some died of the infections of childhood that they were first exposed to in the army. This was particularly true for rural soldiers who had not built up immunities. In addition, camp diseases like dysentery, malaria, and diarrhea spread through the troops in camps and in hospitals.

For the burial of the Union soldiers contributions totaling over $70,000 were submitted from 18 Northern states to the administrators of the Antietam National Cemetery Board. With a workforce consisting primarily of honorably discharged soldiers, the cemetery was completed by September 1867. The official version of the ceremony is included in this text. Susan Trail, citing the Boonsboro Odd Fellow and other newspapers, notes however that the ceremony did not end with the harmony and good feeling reported by the Trustees, and the partisanship and ambivalence that many in Maryland exhibited towards the war led to general dissatisfaction with the ceremony. The fact that the governors of Pennsylvania and New York, states with the largest number of men buried in the cemetery, were not included on the program added to the division. And it was not until almost 10 years later that a cemetery was dedicated for the Confederates who died at Antietam and other locations in Western Maryland.

This list of those interred is organized by state. The dead were identified by letters, receipts, diaries, photographs, marks on belts or cartridge boxes, headstones and by interviewing relatives and survivors. There are over 1700 unknown soldiers. Commissioned officers have a separate entry. There is a listing too of the Regular U. S. troops, the professional army that existed before the war began. They were involved in the fight for the middle bridge across the Antietam. The amount of information on each individual is limited, but some states provided some additional information – for example Michigan provided the town the soldiers were from, other states added the age of the deceased. Cause of death for battlefield causalities is usually restricted to “killed in action” or “died of wounds”. Few other causes of death are given, other than an occasional “Died of typhoid fever” or “Died of sunstroke”.

Resources

Linderman, Gerald F. (1987). Embattled courage: The experience of combat in the American Civil War. Free Press.

Nelson, John H. (2004). “As the grain falls before the reaper”: The federal hospital sites and identified federal casualties at Antietam. Available from 345 E. Antietam St, PMB #174, Hagerstown, MD 21740.

Scott, Harold L. (1995). The Civil War hospitals at Cumberland and Clarysville, Maryland. Cumberland, Maryland: H. Scott.

Trail, Susan W. (2005). Remembering Antietam: Commemoration and preservation of a Civil War battlefield. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland. Available at Western Maryland Room, Washington County Free Library.

Thanks to Susan Trail of the National Park Service, the Washington County Historical Society, the Edward G. Miner Library, University of Rochester Medical Center, Albert Feldstein, and the City of Cumberland.